PHILADELPHIA — President Joe Biden has been scooping up record-making donations and plowing the money into an expanding campaign operation in battleground states that appears to surpass what Donald Trump has built thus far.

Flush with $71 million cash at the end of February — more than twice that of Trump’s campaign — Biden parlayed his fundraising advantage into a hiring spree that now boasts 300 paid staffers across nine states and 100 offices in parts of the country that will decide the 2024 election, according to details provided by the campaign.

Trump’s advisers would not disclose staffing levels, but his ground game still seems to be at a nascent stage. His campaign hired state directors in Pennsylvania and Michigan last week, people familiar with the recruitment process said.

Combined, the Trump campaign and Republican National Committee have fewer than five staff members in each of the battleground states, said two Republicans familiar with the committee and the Trump campaign’s organizational structures in 2020 and 2024.

At this point in 2020, the Trump Victory organization already had state directors, regional directors and field organizers on the ground in battleground states, testing field operations and activating volunteers, the two people said.

“This is like comparing a Maserati to a Honda — 2020 had staff and the bodies in place to turn out the vote,” one said. “This current iteration is starting from ground zero, and we’re seven months out from the election. It makes no sense and puts them at a huge disadvantage to Biden, who is staffing up in droves.”

The start of the general election campaign illustrates how Trump and Biden are waging different bets on the path to victory in November.

Beset by low approval ratings, Biden’s view is that a muscular campaign operation will impress upon voters that he’s championed popular policies and will propel them to completion if re-elected, his advisers said. The question is whether brick-and-mortar offices and phone banks will be enough to overcome nagging doubts about his age and fitness.

Trump faces a different predicament. His political strength has always been rooted more in an emotional bond with his loyal base than in any political apparatus. He’s running strong in the polls, but is awash in dramas, distractions and several ongoing trials.

A chunk of pro-Trump fundraising goes toward legal fees; next week his first criminal trial is set to begin. Since taking over the Republican National Committee last month, his team jettisoned dozens of staff members with the proviso that they could reapply for their jobs.

Both camps say they’re confident about their prospects — even as their allies on the ground are more guarded.

Waiting for the start of a ceremony marking the opening of Biden’s Pennsylvania state campaign headquarters in Philadelphia on March 30, Joanne Waters, 62, said, “I’m a little bit nervous.”

She said she planned to help canvass neighborhoods on Biden’s behalf, make calls to voters and do “whatever they need me to do.”

“I’m anxious to know what the strategy is so we can get folks out to vote, and I’m particularly concerned about the youth vote,” she said.

Sam DeMarco, the Republican chairman in Pennsylvania’s Allegheny County, said in an interview that he did not expect to see full staffing from the Trump-RNC campaign until the summer.

“The team that gets more of their voters to the polls is the team that’s going to win,” DeMarco said. “The Democrats have a significantly better get-out-the-vote infrastructure.”

Trump’s fundraising has been picking up, potentially helping him mount a more competitive ground game if he chooses. His campaign and the RNC said last week they raised more than $65.6 million in March and ended the month with more than $93.1 million on hand.

Trump hoped to get another fundraising jolt last weekend, courtesy of a fundraiser in Palm Beach, Florida. His top advisers said the event at the home of billionaire hedge fund investor John Paulson grossed $50 million for Trump’s campaign, the RNC and other pro-Trump entities.

That sum is nearly twice as much as Biden reeled in last month in a celebrity-rich fundraiser in New York City featuring the president and his two most recent Democratic predecessors, Barack Obama and Bill Clinton.

‘Old victory model’

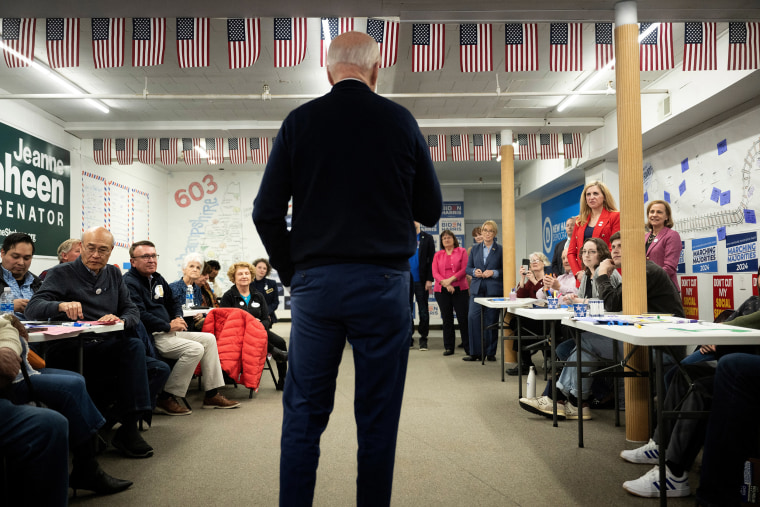

The opening of Biden’s Pennsylvania headquarters had a celebratory feel. Speakers led the crowd in chants of “Fired up; ready to go!” — the anthem of Obama’s successful 2008 presidential bid.

“I’m blown away by how beautiful it is,” Biden campaign manager Julie Chavez Rodriguez remarked at the entrance to a suite of offices in a tony building near City Hall. Signs reading “Stop Trump” decorated the doorways. The president, she said, “often says he hasn’t had campaign offices this nice, but he knows it’s critical,” Chavez Rodriguez added.

Coupled with an advertising blitz in these same swing states, Biden advisers believe he enters the general election phase better positioned to mobilize undecided voters and get them to cast ballots.

In the latter half of March, after both Biden and Trump became their parties’ presumptive nominees, the Biden campaign spent $5.4 million on advertising in Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, according to AdImpact, which tracks campaign spending. By contrast, the Trump campaign spent $34,000 in one state, Georgia, which he narrowly lost in 2020.

Biden’s fundraising success gives him the luxury of placing strategic bets in the hope they pay off. Two of Biden’s 14 Pennsylvania campaign offices are in Lancaster and York counties, both of which Trump won in 2020. Biden may carry neither swath of red Pennsylvania, but cutting into Trump’s support through intensive voter outreach could help him win the state in a close race.

“It’s not just Philadelphia and Pittsburgh,” Pennsylvania Gov. Josh Shapiro, a Democrat, told NBC News in an interview. “They’re opening up an office in Lancaster, which shows they’re willing to compete everywhere in Pennsylvania, and I think they can.”

Getting the word out about Biden’s record, he acknowledged, is “a work in progress.”

Whether an ample ground game is enough to win re-election is far from clear. Hillary Clinton also enjoyed a formidable fundraising edge in her race against Trump in 2016 yet went on to lose. (She, too, opened an office in Lancaster — actor Ted Danson was a special guest — albeit a month before the election). And the machinery that Biden is putting in place faces a bigger test than in 2020, when he built an early polling lead over Trump and never relinquished it.

This time around, Biden’s challenge may be more daunting. His 40% approval rating as of last month was the lowest of any president since Dwight D. Eisenhower at a comparable point in their term, according to Gallup.

Even loyal Democratic voters concede that Biden is a tough sell.

“I don’t think that many people of color are Trump supporters,” said DeShawn Taylor, 49, an African American physician and Biden supporter who came to a coffee shop in Phoenix recently to hear Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer speak about abortion rights. “But I also know that there’s a lot of apathy in communities of color, because people are struggling and oftentimes don’t see their lives change much, regardless of who’s in office.”

Voters remain largely uninformed about legislation Biden signed upgrading the nation’s roads and bridges and returning manufacturing jobs to the U.S. Many Americans see him as too old for the job. A new obstacle emerged last fall: The war between Israel and Hamas is splintering the Democratic coalition, with Arab American and some younger voters blaming Biden for the civilian death toll in Gaza.

All that amounts to a considerable headwind for a campaign to overcome in seven months, however robust its swing state presence.

“Anyone can open all the field offices they want, but it doesn’t amount to a hill of beans if it’s for Joe Biden, who appears out to lunch and at the helm of record high mortgage rates and an inflation problem that hasn’t been fixed,” said Jahan Wilcox, a Republican strategist.

Team Trump’s strategy appears aimed at conserving cash for a blitz that will begin later in the summer, a former senior RNC official, who was granted anonymity to share his frank assessment of the effort, told NBC News.

“I think they’ve made the decision to go back to the old victory model of saving money, waiting until the end of summer, hiring as we need and then just everyone knows that they’re a paid door-knocker and a phone banker, and if volunteers come, that’s great,” this person said.

Trump’s campaign initially referred questions about state staffing levels to the RNC. The committee did not reveal the number of state offices opened, or staff members deployed, saying it did not want to tip off the opposition.

In a statement, RNC Chief of Staff Chris LaCivita said, “With an operation fueled by hundreds of thousands of small-dollar donors and energized supporters, and without sharing our strategy with Democrats through the media, we have the message, the operation, and the money to propel President Trump to victory on November 5.”

Three days later, Karoline Leavitt, Trump’s national press secretary, issued a statement saying, “The premise that we don’t have paid staff in the battleground states is flatly false. We have paid staffers and volunteer-powered field programs in every battleground state and they are expanding daily. We don’t announce every organizational move in the media, because we aren’t a losing campaign in need of manufactured momentum like Joe Biden.”

‘Tentacles out into the surrounding community’

A look at a few swing states suggests Republicans at this point in the calendar are playing catch-up.

In Michigan, state GOP chairman Pete Hoekstra said last month that the party needed more money, field staff and programs to reach minority voters. By contrast, the Biden campaign has opened 15 field offices in Michigan, with plans to double that number by April 15.

“Showing up is half the battle,” Whitmer told NBC News in an interview. “When you show up you learn from voters what’s important to them. You communicate to voters that you care about them.”

“I know first-hand in Michigan that you have to do the ground game. You’ve got to talk to voters and earn their vote,” she added.

In Wisconsin, Republicans closed a Hispanic outreach center based in Milwaukee; the space is scheduled to become an ice cream shop under new ownership, the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel reported.

For its part, the Biden campaign announced last month it was opening 44 field offices across Wisconsin, hoping to build upon a string of Democratic victories over the past eight years.

Milwaukee Mayor Cavalier Johnson, who is looking to drive Democratic turnout in his city and the surrounding areas, said the build-out is especially important in Wisconsin, where the margins of victory in the last two presidential elections were both less than 23,000 votes.

“If you’re opening offices, that means you have people that are on the ground in those offices who are then being tentacles out into the surrounding community,” Johnson said.

State campaign offices serve myriad purposes. They can be a place people go to pick up yard signs, make calls to unregistered voters, or get the training needed to become effective evangelists when they go door-to-door.

Part of the Biden training regimen involves schooling volunteers in his personal biography so that they can talk more fluently about his life story when they meet voters face to face, campaign aides said.

But state teams also serve a more utilitarian function: making sure that people have a ride to the polls or drop their absentee ballots in the mail. That can be grinding work, but operatives say it can be decisive in a tight election.

“I’ve made to everyone who will listen [the point] that our challenge is changing the mindset of Republicans to get them to request [mail-in ballots] in the first place,” said DeMarco, the GOP chair in Pennsylvania’s Allegheny County. “That’s where not having boots on the ground early, and being able to set up one of these programs, puts us at a disadvantage.”