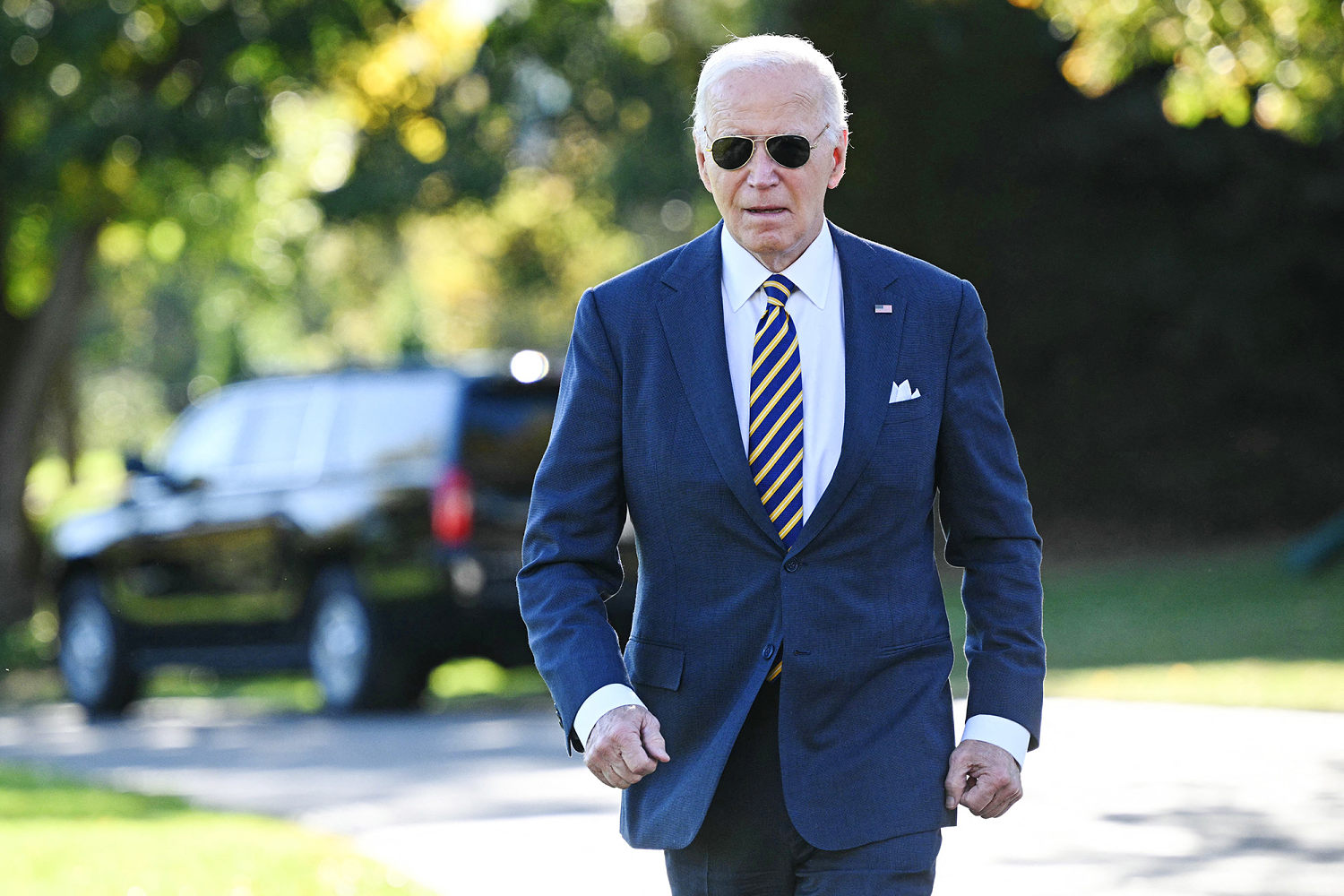

PHOENIX — President Joe Biden delivered an apology Friday for a United States policy that forcibly separated generations of indigenous children from their families for more than 150 years and sent them to federally backed boarding schools for forced assimilation.

“I formally apologize as president of the United States of America for what we did,” Biden said in strident remarks. “It’s long overdue.”

The president’s apology comes in the wake of a years-long investigation commissioned by Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, a member of the Pueblo of Laguna and the first Native American to serve as a Cabinet secretary. Haaland’s grandparents were separated from their families because of the policy.

“We know that the federal government failed,” Haaland said in emotional remarks before Biden was introduced. “It failed to violate our languages, our traditions, our life ways. It failed to destroy us because we persevered,” she added.

The investigation uncovered generations of trauma. It identified the deaths of at least 973 Native American, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian children who attended the boarding schools. In total, the probe identified 417 institutions across 37 states or then-territories that were operational between 1819 and at least 1969.

“Many Indian children suffered physical, sexual, and emotional abuse at these institutions,” the report found. It confirmed that at least 74 marked and unmarked burial sites at 65 school sites.

Biden’s apology comes more than two years after Pope Francis issued a similar apology on behalf of the Catholic church for similar abuses in Canada. More than 150,000 native children were forced to attend Canadian boarding schools.Alex White Plume, 73, former president of the Oglala Sioux Tribe who attended two boarding schools on reservations in South Dakota, told NBC News he would not accept the apology from the president.

“I don’t really see any way where we could accept it, because it doesn’t change anything,” White Plume said.

“We need to survive, and in order to survive, we need our territories back so we could bring back our language and perform the ceremonies that are specific to places in our territory,” he said. “So I don’t want to accept an apology. I want them to be meaningful. And if it’s a meaningful apology, he would say, Okay, we’re gonna investigate the genocide and we’ll establish a process to create protocols on how to go about it. I think something like that would have been more meaningful.”